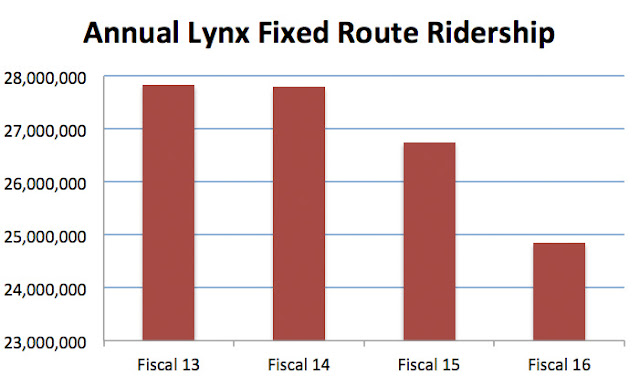

Lynx Ridership Has Dropped Over 10% in Less than 4 Years

Annual Lynx ridership has decreased by nearly 3 million annual passengers since 2013/2014, a Lynxed Together analysis has discovered. This decrease represents a drop of over 10%.

Month over month, ridership has dropped 26 out of the last 28 months, with decreases as high as 12.6% (Jan 15 vs Jan 16). Lynx experienced its' peak ridership month in October 2013, with over 2.56 million riders. In October 2016, ridership barely surpassed 2.02 million, a whopping decrease of 21.3%. January 2017, the most recent month for which data is available, showed a rare 1.1% increase over 2016. but the 2.02 million passengers represented a 15.2% decrease from peak January passengers in 2013.

- Launch of SunRail service

- Lower gas prices

- Ridesharing (Uber, et al)

Let's examine each of these factors.

Some

longer-distance commuters certainly switched from Lynx to the train

when it debuted in May 2014. Indeed, Lynx noted that several

commuter-focused links (routes) were eliminated when SunRail service

started.

However, with the launch of SunRail, 19

links were realigned to provide connecting service to SunRail stations.

Ultimately, most SunRail commuters need a way to get the "last mile" to

their destination, so the majority of any decrease in longer-distance commuters

should have been offset by increases in "last mile" passengers.

Though, ultimately, any decrease in Lynx passengers attributable to SunRail is a wash, and perhaps even a net gain when viewed from a regional/big picture perspective, as these commuters are still utilizing public transit, simply a more efficient mode.

Though, ultimately, any decrease in Lynx passengers attributable to SunRail is a wash, and perhaps even a net gain when viewed from a regional/big picture perspective, as these commuters are still utilizing public transit, simply a more efficient mode.

Lynx

attributes the drop in ridership almost exclusively to lower gas prices.

It's cited at every board meeting, and they've even started including a

graphic in the monthly ridership report that shows year-over-year

ridership data vs the year-over-year gas price.

While

gas price fluctuations may sway a small number of "choice" riders toward

or away from public transit, especially for longer (read: more

expensive) commutes, it's not realistic to think that several thousand

commuters on a typical weekday who have cars in their driveway (with the

corresponding fixed costs of car payments, insurance and

maintenance) are leaving them parked and walking to the bus stop simply

because gas (a relatively small part of the cost of the car ownership

equation) is at $3.

Uber

is a smartphone app that allows you to hire a private driver, on

demand, to take you from door to door. An Uber ride costs roughly 1/3

the price of a taxi, is completely cashless, and allows you to track

your car and driver and their location so you know exactly when your ride

is coming and who is behind the wheel. In short, it's a very

convenient, quick and cost-effective way to get from point A to point B.

Uber debuted in Orlando in early June 2014.

Lynx, on

the other hand, while very cost effective, is rarely a quick or

convenient transportation option. Indirect routings, infrequent service,

and limited operating hours can make a bus ride both time consuming and cumbersome.

Given the confluence

of Uber's arrival in Orlando and the beginning of the decline of Lynx

ridership, we argue that Uber has created a new segment of "choice"

transit riders: Individuals who don't own a car and can't (or won't)

spend money on a taxi, but see value in a quick, cost-effective

door-to-door ride for at least some of their trips. These individuals

likely still use Lynx for some (and maybe even most of) their trips, but

when the weather is poor, they're in a hurry, or for any number of

other reasons, they're willing to pay for a door-to-door ride.

Say, for example, that you work the front desk of a hotel on International Drive, near the Orange County Convention Center. You live near W. Colonial Drive and John Young Parkway. When you get off work at 8 pm, you could catch Link 8. But unfortunately, you've just missed the 7:56 departure, so you've got to stand at the bus stop until the 8:25 pm bus. Then, you've got a slow, winding ride that takes you up International Drive to Oak Ridge Road, over to Rio Grande and through Americana, onto the traffic-choked Orange Blossom Trail and around Paramore, finally arriving at Lynx Central Station at 9:20 pm. It's been an hour and 20 minutes since you got off work, and you're still not home. You just missed Link 49, which departed at 9:15, so you've got another wait, this time for Link 48. You depart Lynx Central Station at 9:45 and at 9:57, almost two hours after you clocked out, you finally get off the bus to walk the last few blocks home.

Or, you could pick up

your smartphone, open the Uber app and request a ride. An Uber will

probably arrive in less than 5 minutes and take you directly home

(likely 15 minutes or less). You're home in 20 minutes (that's before

that 8:25 bus even arrived) and it cost you about $12.

Which would you pick?

While

all three of these factors (and perhaps other influences that we

haven't considered) are impacting Lynx ridership to some extent, we

believe that this new segment of choice riders created by the

ridesharing economy are the biggest factor.

Earlier

this month, we sat down with Lynx CEO Edward Johnson for an exclusive

interview. We asked him about the ridership trends.

"A

lot of that is following the national trend," Johnson said. "When you

look around the country, you see many transit agencies' ridership

decreasing and that's tied into the ... lowering of gas prices. ...

That's one of those things that we in the transit world experience."

When

asked if the rise of ridesharing was a factor, Johnson said "There very

well might be some decline in ridership due to Uber, we just don't have

the analysis that gives us a very good picture of that.

"Even

with Uber ... it still ties back into the overall transportation

program. We don't necessarily look at them as being competitors."

Asked

whether cutbacks were possible due to the downward ridership trend,

Johnson indicated that it may result in resources being reallocated. "If

we see a decline in ridership in a particular area, maybe the service

volume may get decreased so we can allocate those financial resources

and put them in areas" with a bigger need.

"What we

want to do is have one transportation system for our community. They

don't care if it's Uber, Lyft, SunRail, what have you," Johnson said.

"What they care about is can they get from point A to point B."

Well they will grow to at some point in the future. The drop happened because of the customers, but as they increase, we will see a big rise in that number.

ReplyDelete